The Mystery of Similarity

Despite the grand, cosmic conclusions, Platonism begins from very simple, ordinary observations. These observations are so simple and ordinary that we are liable to miss how mysterious they really are and how difficult it is to understand the deeper structures of reality that must be in place for these simple, ordinary observations to hold true. Part of the enchantment that Socrates weaves over our minds with his persistent, annoying questions is that he makes the simple and ordinary seem difficult and strange in order that we might begin to think about the ordinary for the first time. Among these ordinary mysteries—and leading straight to the heart of Platonism—the common experience of similarity is perhaps the most strange of all.

I see, for example, two dogs. My mind immediately grasps that Fido is the same kind of animal as Rex because the two are similar in many ways. And yet, I also grasp that they are not completely the same. I see that I am not dealing with one and the same dog, but two different dogs. For the two dogs to be two dogs rather than just one dog, they must be not the same in at least some way. I may seem to be stating the obvious, but a great frontier of discovery waits for us just beyond the crest of the hill if we push forward a little with these observations: For the dogs to be similar but not the same, there must be something about them that is the same. The sameness, however, must be a strange kind of sameness. It must be a sameness that spans across difference. Furthermore, my mind must be able to latch onto this sameness, or else I would be unable to categorize them as members of the same species.

A first temptation would be to say that I observe particular attributes in Rex and particular attributes in Fido and I compare these attributes. I see, for example, that Rex is a certain size and I see that Fido is a slightly different size. So I compare size-of-Rex to size-of-Fido and see that they are close. Likewise, I see that Rex has a certain shape and Fido has a slightly different shape. I compare the shape-of-Rex to the shape-of-Fido and see that they are close without being quite identical. This kind of response, however, just pushes the problem back one step. Instead of figuring out how two different dogs can be similar, we are now figuring out how distinct attributes in different dogs can be similar. To answer this second question we will need, again, to say what is the same about the similar attributes across their slight differences. If we apply the same logic again, we would need to have attributes of attributes, and then attributes of attributes of attributes. Such an answer would be silly. It would also be viciously circular, which, for serious philosophers, is much worse than being silly.

Furthermore, if my mind is only grasping attribute-in-Rex and attribute-in-Fido, i.e. features that are wholly peculiar to the one or the other, then I’m really only noticing difference and multiplicity rather than sameness and unity, and that’s just not what we actually experience. Anyone who has ever seen two similar things can tell you that the mental grasp of similarity is instantaneous and basic. It isn’t a deduction—even a very rapid deduction—from some more basic data of experience. In fact, if our “basic data” only include the observation of discrete, differentiated things and attributes, without ever grasping unity between them, we would never be able to make a deduction from difference to unity, no matter how many instances we observe.

At this point in the conversation, one often encounters an interesting “just-so story.” It goes like this: “Well, you see, you can grasp the similarity between two dogs now, as an adult, because you already have the concept of ‘dog’ that you learned as a baby. Your recognition is instantaneous because this category is so ingrained that you apply it automatically. It wasn’t always this way, however. As a baby, you had to learn this concept by seeing one discrete animal, then another, then another, hopefully with a helpful mother pointing and saying ‘dog’ each time. Over time, you got the hang of it, and now the similarity that you’re grasping is just the application of your learned concept.”

There are numerous problems with this “just-so story,” but the main problem for our present purposes is that it entirely misses the point. We aren’t asking about the way that we come to acquire words or concepts. We are asking how it is that the mind is capable of grasping similarity and what the world has to be like for this to be possible in the first place. If the baby in the just-so story were incapable of seeing that dogs were similar to begin with, he would be unable to start picking up on what his mother was doing pointing at such things. Further, he also needs to hear the similarity in the sounds his mother is making and match similar sounds to similar objects. Without this more basic capacity for recognizing similarity, the baby would not be able to even start the process of learning words and forming concepts. The capacity for recognizing sameness-across-difference has to be more primordial than our capacities for concept and word formation because these latter capacities are entirely incoherent without it.

Furthermore, we can simply bypass the just-so story entirely and ask the same annoying questions about similarity to entirely new categories that we don’t have words or concepts for. Even as adults, we very frequently recognize similarity between things that are strange or unfamiliar. How else could we have that moment of wonder when we start to discover an entirely new kind of thing? We couldn’t have this wonder if our ability to see similarity depended upon already knowing what kind of thing it is and what to call it.

What, then, is the mind latching onto when it exercises this capacity? Allow me to switch the example in a way that will raise some thorny issues in a later essay but that, for now, will help to achieve the insights we are looking for.

Consider the famous piece of music, “Waltz for Debbie,” which Bill Evans wrote for his niece. The most well-known version of this song appears on an album of the same title, which was recorded during a historic live performance at the Village Vanguard in 1961. The first appearance of the song, however, occurs on Evans’ debut album New Jazz Conceptions, which he recorded in 1956. Listen to just the first four bars of these two recordings several times and revel for a moment in the beautiful opening chords.

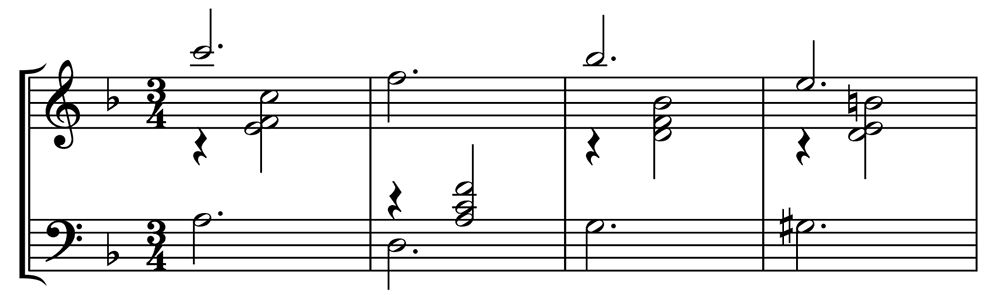

Although these two recordings are four years apart, at different pianos, and in completely different settings, you can clearly hear that they are the same song. Again, however, the obvious is strange. From one perspective, a song is obviously something we hear. This means that particular air vibrations have to enter our ears at a particular time. If different vibrations enter our ears at a different time, that would be a different song. From another perspective, however, we can easily recognize that two totally different performances at different times are one and the same song. According to this latter conception, the song itself is paradoxically not made of sound. We can transcribe the first four bars of what we hear like this:

A skilled musician reading these notes can easily recognize the same song again, even though the printed notes make no sound at all while he reads them.

According to this meaning, then, the “song” is something we grasp with our minds rather than hear with our ears. It is an inner structure that shows up in the 1956 recording, the 1961 recording, and the written sheet music. Using modern lingo (and not without some risk of misunderstanding), we might say that the song itself is pure information that is then encoded in all these different media. It is the same information because it is isomorphic across instances.

This fundamental isomorphism across diverse instances remains even when we notice variations between them. There are subtle differences in the playing, for example, between the live performance and the studio recording, but it is obviously the same song. Less obviously, however, we can hear the same structure even when Evans modulates from A major to F major during an improvised 1971 version, or when the Oscar Peterson Trio performs their own version during a 1964 European tour. It takes a skilled ear to hear the same jazz standard when the improvisation and creative variation become more and more wild, but underneath, the deep structure of the song is the same.

What our minds can do with jazz it can do with dogs. And we do it all the time. Whenever we see or hear that two things are the same, we are doing more than merely seeing or hearing with our eyes and ears particular colors and sounds. We are apprehending with our minds an intelligible unity that shows up across multiple diverse instances.

This is one of the cornerstone insights in the foundation of Platonism. We will have much more to say about this idea of “intelligible unity” as we clarify several misconceptions, introduce technical terminology, and draw numerous conclusions. Throughout, however, we must keep our footing in the ordinary experience of similarity lest we become lost in a verbal morass of terms and dogmatic formulae. Keep listening to Bill Evans (which is good for you in lots of ways), and keep thinking about what it means for all similar performances to be different manifestations of the same song.