Tell Me What to Want

Whenever I become frustrated or unhappy with my life I go hunting. I have friends who seem to find some solace hunting animals in the woods on cold wet mornings, but I find that whole affair all too cold and wet. Instead, I hunt myself. Or rather, I hunt a fantasy version of myself that I glimpse far off at rare moments as a rapidly shifting ghost flitting among digital trees. This kind of hunting brings me no solace at all, but I don’t know how to stop.

The trouble is that I don’t really know what I want, I desperately want to know what I want, and there are numerous services offering to solve this trouble for me by promising a variety of visions so compelling that I will finally know what I want whenever I reach the bottom of the feed.

These algorithmic seducers bewitch us with a new kind of sorcery. It’s all marketing and capitalism, of course, but the old kind of marketing was considerably more transparent, at least on the surface. In the old way of marketing sorcery, people were enticed to buy goods and services. The method was always the same, although it was done with more or less nuance and sophistication: “Purchase this and your life will be better.” In order to generate the feeling of this if-this-then-that purchasing promise, the successful advertisement must produce in the viewer some vision of a way his own life could be better.

In the bright colors and peppy music of the Coca-Cola advertisement, I see for just a moment what a bright and peppy life might be like. It isn’t stated exactly, and I don’t see it squarely. I see it sidelong out of the corner of my eye, a fuzzy suggestion, a whisper of hope.

In the dark colors and serious music of the Lexus commercial, I see what I could be if I were a sophisticated, wealthy urbanite who drives up to fine restaurants at some metaphysically impossible time after midnight when the Manhattan streets are completely empty.

Anyone with an ounce of intelligence and self-reflection can see through this, although it takes a little more than an ounce of self-discipline not to fall for it anyway. The algorithmic feeds, however, take this old sorcery and raise it to the level of our metadesires: What do we want to want?

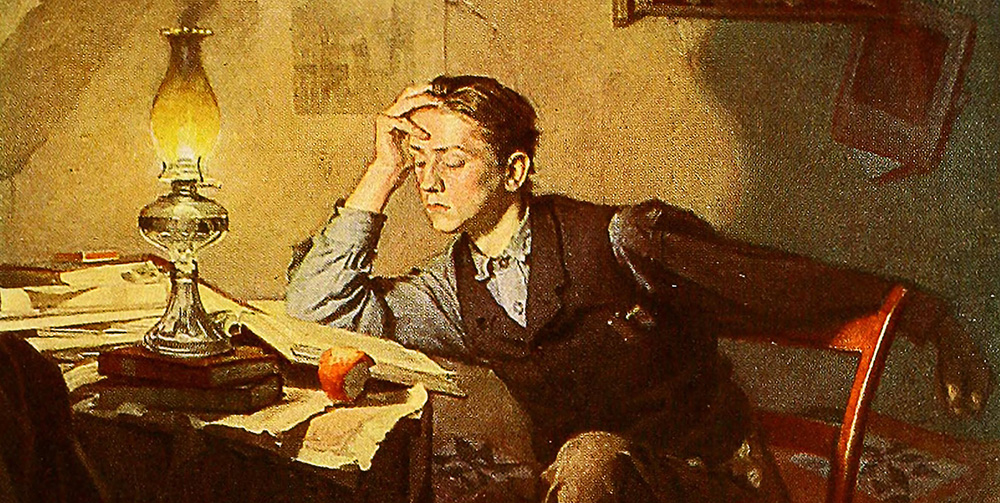

I have desires, of course, for sweets and entertainment and a flattered ego, but most of these I don’t really want to want (or at least I want to want them less). What I hunt for on YouTube and stalk on my friend’s feeds, however, is something more subtle. I’m trying to figure out what I really want, what I want to want, and I’m anxious and unhappy because I don’t yet know.

When I started to fill my old Victorian house with furniture, I started mood boards on Pinterest filled with clipped images of wallpapers, curtains, leather armchairs, tall custom bookcases, artifacts, and oriental rugs. I scoured hours of Design Notes videos on YouTube looking for those split-second camera shots that gave me just the right feeling. I walked for miles upon miles through disarrayed aisles at Peddlers Malls and antique markets, turning left and right, left and right, like a sniffing dog on a sent.

This behavior has a kind of rationality to it. I had just spent money on a home for my family. I needed to furnish this home and I wanted it to be lovely. In order to be lovely, the new things needed to go together, and in order to do this I needed to decide upon a unified aesthetic. The difficulty is that I did not fully know which aesthetic I wanted exactly or which things would fit with it. I needed, therefore, to do considerable research to figure out what I really wanted and how best to achieve it with the resources I had available—as I said, “a kind of rationality.”

But then the madness sets in. It turns out that the number of interior design images on Pinterest is greater than the number of protons in the universe. After literal days refining my sense of what I wanted, the sought-for sense always seemed to remain forever just around the corner. If I knew what I wanted, then I could get to work creating it, but while the madness lasts, the beginning of that creative work is forever postponed until the goal can be clearly seen—and for some reason Damask silk wallpaper can be found for sale in every color of the rainbow except for dark green (you can find it on walls in houses, to be sure, but those existing walls must have permanently exhausted the supply).

Instead of simply sitting down and determining what was possible in my circumstances and what I wanted, like a mature, reflective person, I wanted the algorithms to momentarily forestall the effort of decision by telling me what to want.

This is one problem when it’s the decoration of a house, but it’s a much deeper problem when it’s my whole life. Every time I watch a YouTube video on any subject, I always have one eye on what it is telling me about what to want. Oh the joy when I actually like what it’s telling me, even just a little. When this happens, I know that the promised vision is “coming up next.” When I finally see it, I know that I will have the vibe of my inner mood board dialed in just right; then it will all be settled; then I will wake up in the morning with gusto because I’ll know what I want for the day; then I’ll know how to dress, how to carry myself, what to say; then I’ll know who I am.

YouTube doesn’t want this to happen, of course, and none of the other algorithmic feeds do either. If I figured out what I wanted, then the game would be up, I would have no reason to keep scrolling, I might look up to see real birds in an actual park, and the whole codependent relationship would suddenly end. So the content can’t be too satisfying. In fact, it needs to be mostly unsatisfying and banal, only hinting occasionally at a version of myself that I might one day admire.