Dead Friends

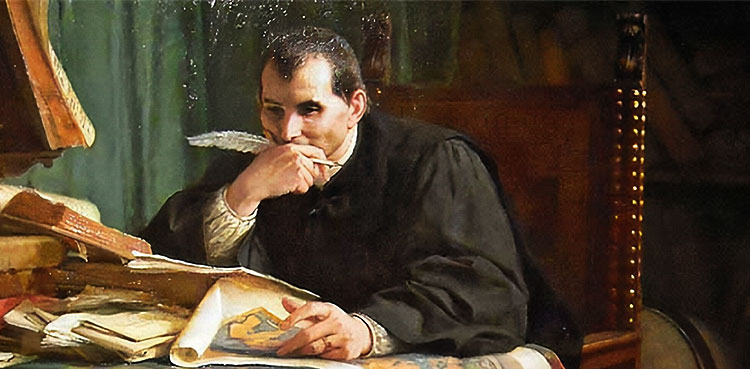

I play a little game with my dead friends. I collect their faces and attach them to my notes on their body of work. The first thing from Wikipedia won’t do. I search carefully for a portrait that strikes something inside me. John Singer Sargent said that a portrait is just a picture with something wrong about the mouth. The portraits that I collect are just faces with something right about the eyes. It’s the eyes that tell me that we can be friends.

I like to see their faces again and again when I open my notes. It’s like meeting them for lunch. I am reminded of their presence, of their personal reality, behind the words that I read. When reading T.S. Eliot, for example, it helps to see his parted hair and the elegance of his necktie.

I am surrounded by them spiritually in my memory and surrounded by them physically on my walls. Evelyn Waugh, slouching deeply into his chair, diffidently tilts his cigar in my library. C.S. Lewis, in a woodblock print, comforts me with a gentle smile every time I walk down the little hallway from the butler’s kitchen to the bathroom. Chopin tells me that I can do better from his little perch above the piano on the mantle in the music room. And Dante’s Tuscan visage, even more commanding and austere in the hard white of his Parian bust, oversees the successes and failures of my writing in the office.

How can one survive without such friends? Sometimes I do go out. Sometimes I see that, apparently, many people do live a kind of life without dead friends. But it remains an impenetrable mystery to me how this is possible. The talk at parties with living people is just not that interesting.

One of my oldest friends, A.G. Sertillanges introduced me to a story about Machiavelli (a friend who, though much maligned, I stand by nonetheless). Every day when Machiavelli would return home, he would go to his study. Before crossing the threshold, he would take off his everyday clothes, covered in the mud and mire of the workaday world. He would prepare to enter his study by donning “regal and curial robes.” Thus dressed “in a more appropriate manner,” he tells us:

I enter into the ancient courts of ancient men and am welcomed by them kindly, and there I taste the food that alone is mine, and for which I was born; and there I am not ashamed to speak to them, to ask them the reasons for their actions; and they, in their humanity, answer me; and for four hours I feel no boredom, I dismiss every affliction, I no longer fear poverty nor do I tremble at the thought of death; I become completely part of them.

Even though he died on the 21st of June, 1527, I understand Machiavelli completely. I understand him better, in fact, than I understand the actions of those I encounter in the grocery store.

The faces around me and in my notes remind me that my dead friends live with me still. The vibrancy of their life is what I see in their eyes. They do not haunt me like the gibbering shades that Odysseus summons from the edge of the underworld, mindless and drained of all their blood. No, their blood is thick enough and flowing in their words, their art, their song. The community of dead people is a community of life. And under their tutelage, I hope still to live a fuller life than I have lived before.