The Unread Library

The only thing preventing me from reading every volume in my library is my death. If it comes soon, the number of unread volumes will be quite large. If it comes many decades from now, the number will be many times larger.

I fear you will think this situation arises because I never read, but I assure you that I do little else. Only illiterate people read all their books.

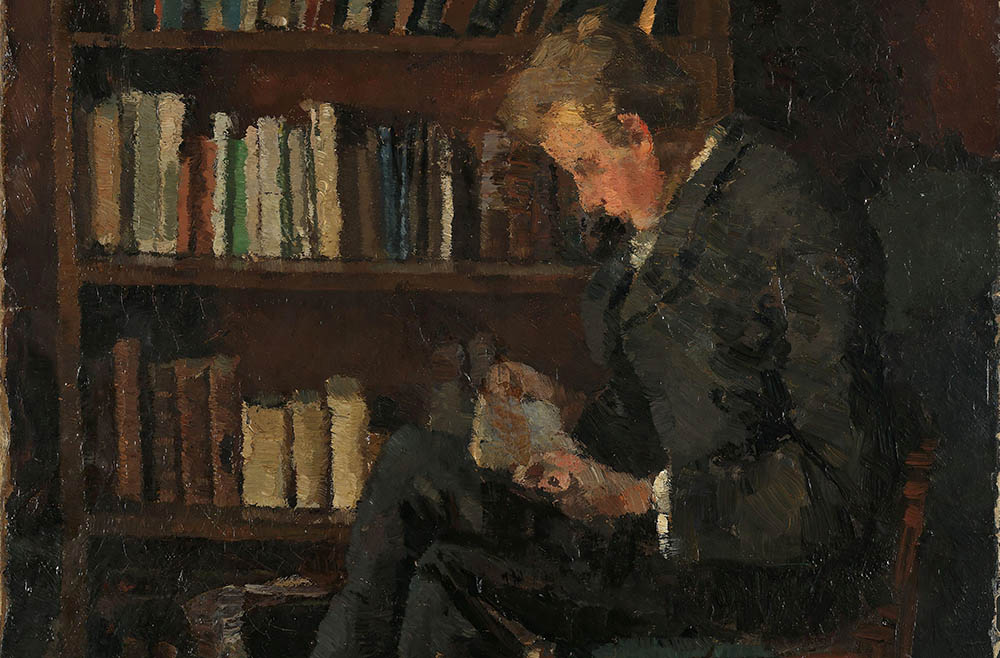

The unread volumes surround me. I enjoy their companionship. They whisper to me pleasant invitations. They sometimes chide and even scold, but I enjoy the bracing effect of these communications too. They are not bigots; they mix company amicably enough with the minority population of books that I have read. I suppose I am the bigot, though, since I have a definite prejudice in favor of the majority.

I rarely read a book a second time. I read slowly the first time and savor every paragraph, treasuring up what I can permanently store in my heart, if the book is any good. If the book is very good, I will read it ten times: Plato’s Symposium, the Four Quartets or Brideshead, for example. But such books are rare because the price of a second read is the first read of something else.

I am a greedy socialite. I would prefer to make a friendship out of a half-known charming acquaintance than to deepen a friendship with a book that I found merely charming. I have my circle of intimates, but they are a snobbish clique.

Some unmet celebrities I feel that I have known for years. They are the people one sees across the room at banquets and one knows by reputation. The joys of anticipation in such cases are among life’s most refined pleasures. Proust, for example, sits on the shelf in his winsome red leather binding. He glances across the room at me from time to time with a smile, and I know that soon, very soon, I will find my way across to him.

There is more than a hint of financial irresponsibility in all this. Can one really justify continued expenditure on what will be left unused? In a letter to Jacob Blatt, Erasmus once explained his growing obsession with ancient Greek books: “The first thing I shall do, as soon as the money arrives, is to buy some Greek authors; if any is left, I shall buy clothes.”1 Only a financially irresponsible man like Erasmus can have his priorities straight.

How dull life would be if it were not like this. Imagine the sadness that would follow if one actually came to the end of one’s books. Having read them all, what then? One could, I suppose, circle back around and cover the same ground again, but the nature of the territory would be changed because known. A certain kind of adventure only happens the first time, and the sense of all the first times still to come gives our journey hope, excitement, mystery, and a certain elan. Even the familiar meadow gains in richness when the unexplored forest stands behind it.

No, I will keep buying more books, and I will keep buying them faster than I can read them until the Lord takes me. I will savor their invitations and their whispers will be my muse.

Statimque ut pecuniam accepero, Graecos primum autores, deinde vestes emam.↩︎